What is Rasa?

In Sanskrit, Rasa literally means “essence,” “flavor,” or “juice.” But in the context of the Natya Shastra, rasa refers to the emotional flavors or sentiments that a work of art (like drama, dance, or music) evokes in its audience.

The sage Bharata Muni, in the Natya Shastra, proposed that the ultimate goal of performance arts is to evoke these rasas, creating a shared emotional experience between the performer and the audience. This is not just entertainment but a spiritual and psychological experience — a rasa can purify the mind, elevate the soul, and connect people through universal emotions.

The Theory of Rasa

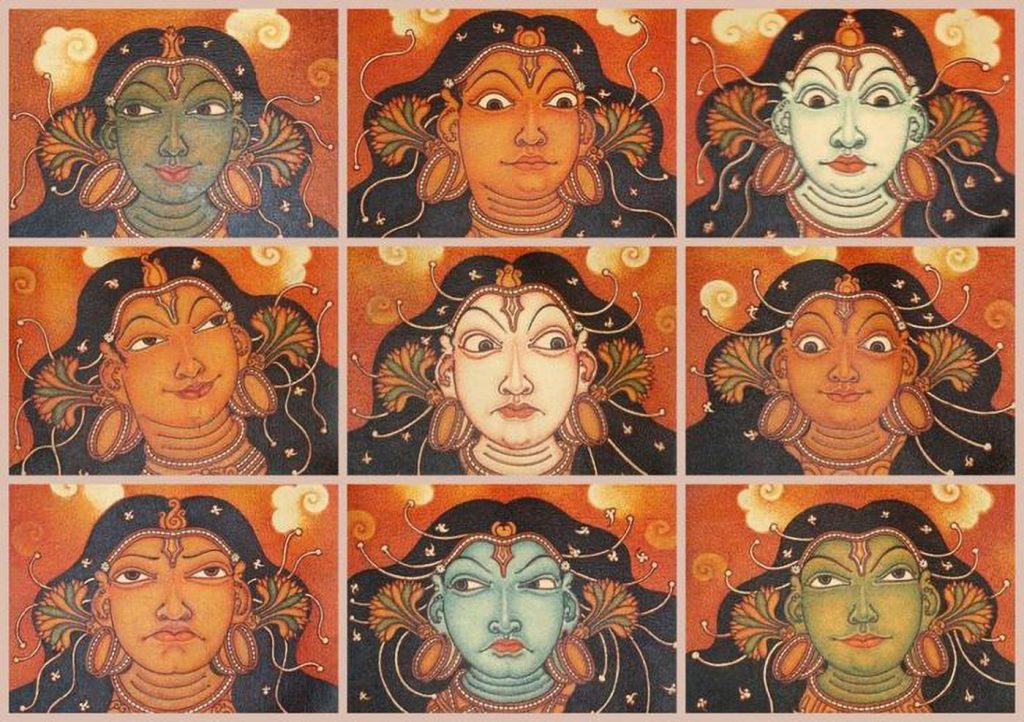

Bharata outlined eight primary rasas, which later scholars expanded to nine. Each corresponds to a specific emotional state or mood. These are:

| Rasa Name | Associated Emotion (Bhava) | Description |

| Śṛṅgāra | Love, Attraction | The emotion of romantic love and beauty |

| Hāsya | Laughter, Mirth | The emotion of humor and joy |

| Raudra | Fury, Anger | The emotion of anger and aggression |

| Kāruṇya | Compassion, Sorrow | The emotion of sadness and empathy |

| Bībhatsa | Disgust | The emotion of revulsion and aversion |

| Bhayānaka | Fear | The emotion of fear and anxiety |

| Vīra | Heroism | The emotion of courage and valor |

| Adbhuta | Wonder, Amazement | The emotion of surprise and curiosity |

| Śānta | Peace, Tranquility | The emotion of calmness and spiritual serenity |

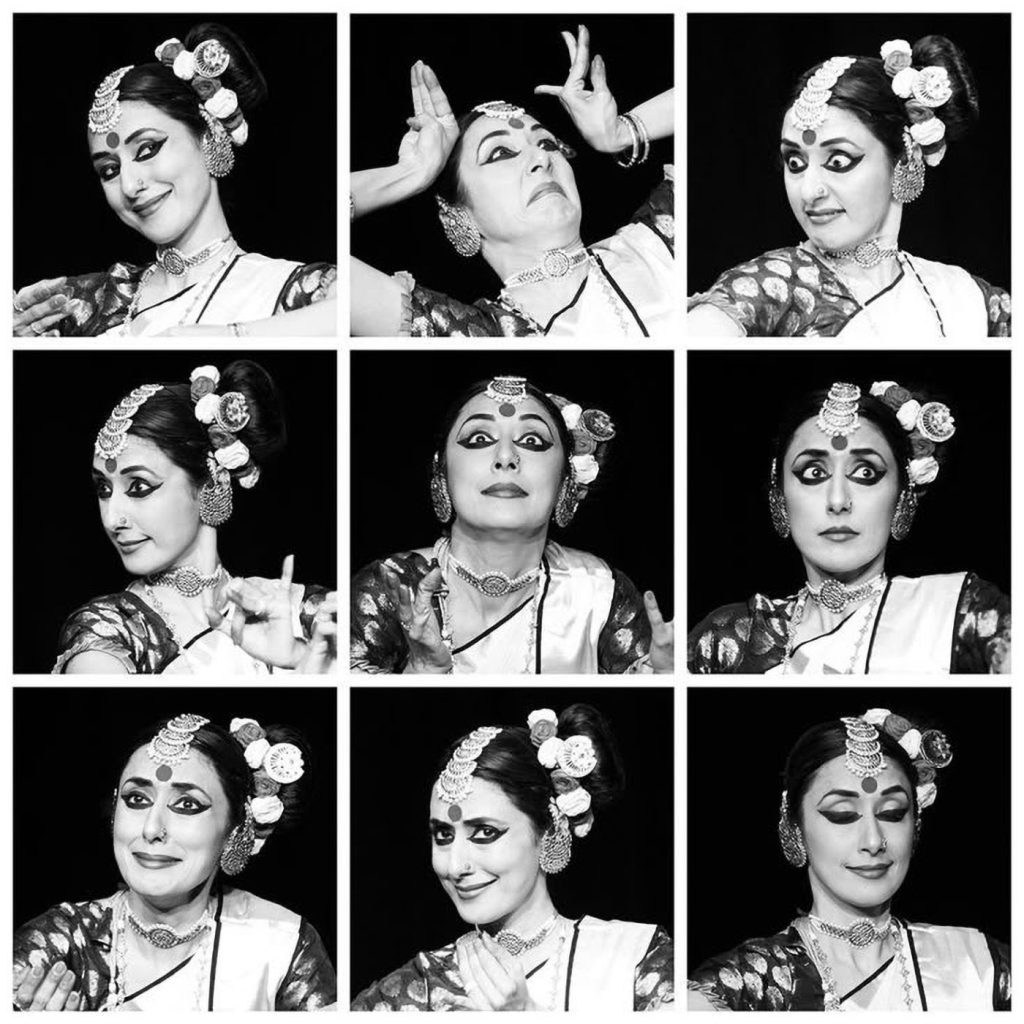

How Rasa Works in Performance

Rasa is not just about expressing an emotion; it is about evoking a corresponding emotional experience in the audience.

- The performer uses Bhavas (the physical and mental states or emotions) through facial expressions, gestures (mudras), body language, voice modulation, and rhythm.

- These Bhavas trigger the Rasas in the viewer, leading to a shared emotional journey.

Example 1: Śṛṅgāra Rasa (Love and Beauty)

In a classical dance like Bharatanatyam, a dancer might depict the romantic longing of Radha for Krishna. Through subtle eye movements, gentle smiles, and delicate hand gestures (like the Pataka mudra symbolizing blossoming love), the dancer conveys feelings of attraction and affection.

The audience, immersed in the performance, feels the essence of love — not just observing it but experiencing the rasa.

Example 2: Vīra Rasa (Heroism)

In a Kathakali performance, a warrior like Arjuna or Bhima from the Mahabharata might be shown preparing for battle. Bold, expansive movements, fierce eye expressions, and strong foot stomps evoke courage and valor.

The audience feels inspired, their hearts stirred by the hero’s bravery.

Example 3: Kāruṇya Rasa (Compassion and Sorrow)

In Odissi, a dancer might portray Sita’s sorrow during her exile in the Ramayana. The dancer’s downcast eyes, slow movements, and quivering lips express deep sadness, inviting the audience to empathize and feel compassion.

This shared sorrow purifies the heart, one of the Natya Shastra’s aims.

Rasa and the Ninth Rasa: Śānta (Peace)

The Śānta rasa or peaceful rasa was added later by scholars and is considered the highest rasa, representing spiritual tranquility and bliss. It’s often the emotional climax of a performance that moves beyond worldly emotions to a meditative state.

Why Rasa is Unique

Unlike Western theories of emotion in art, which often focus on narrative or psychological realism, Rasa emphasizes a collective aesthetic experience. The audience is not a passive observer but an active participant, emotionally engaged through the performer’s skill.

Summary: The Power of Rasa in Indian Performing Arts

- Rasa is the core aesthetic experience — the “taste” or “flavor” of an emotion evoked by art.

- It connects performers and audiences through shared human emotions.

- It transforms a performance into a spiritual experience, purifying the mind and elevating the soul.

- Classical dance, theatre, and music are designed to awaken rasas through precise gestures, expressions, rhythm, and storytelling.

- Understanding rasa enhances the appreciation of Indian classical arts, revealing their profound emotional and philosophical depth.

Mudras and Their Role in Expressing the 9 Rasas

According to Natya Shastra there are 67 mudras available. Some of them are taken here for example purposes. The details about mudra will be available in Natyasashtra part 5.

1. Śṛṅgāra (Love & Beauty)

- Mudras:

- Hamsasya (thumb and index finger touching, others extended) — to show holding a flower or delicate touch.

- Katakamukha (thumb, index, and middle fingers together) — used to depict holding a garland or jewelry, symbolizing romantic gestures.

- Example: Expressing Radha’s affectionate glances towards Krishna by gently holding flowers or jewelry with these mudras.

2. Hāsya (Laughter & Joy)

- Mudras:

- Alapadma (open palm) — often combined with smiling expressions to show playfulness or teasing.

- Kapitta (thumb and middle finger touching) — used for mimicking laughter or cheeky gestures.

- Example: A dancer portraying a humorous character might use rapid changes of these mudras with bright smiles to evoke laughter.

3. Raudra (Fury & Anger)

- Mudras:

- Mushti (clenched fist) — symbolizing aggression and readiness to fight.

- Simhamukha (lion face) — representing ferocity and wrath.

- Example: A warrior character like Bhima expressing rage and power through strong, forceful fist gestures.

4. Kāruṇya (Compassion & Sorrow)

- Mudras:

- Pataka (flat palm) with downward movement — expressing sadness or mourning.

- Arala (index finger bent) — used to indicate tears or shielding the face in grief.

- Example: Depicting Sita’s sorrow in exile by slow hand movements combined with downcast eyes and these mudras.

5. Bībhatsa (Disgust & Aversion)

- Mudras:

- Chinmaya (tip of thumb and little finger touching) — can depict disdain or something unpleasant.

- Ardhapataka (half-flag) — used to show rejection or pushing away.

- Example: Portraying disgust at an evil character’s act by turning away with these mudras.

6. Bhayānaka (Fear & Anxiety)

- Mudras:

- Kapitta — combined with trembling fingers and wide eyes to depict fear.

- Tripataka (ring finger bent) — to show caution or alertness.

- Example: A dancer showing fear of an impending threat might use these gestures to signal trembling and alertness.

7. Vīra (Heroism & Courage)

- Mudras:

- Mushti — clenched fist showing strength.

- Simhamukha — fierce, lion-like face for boldness.

- Example: Arjuna preparing for battle, using forceful fist gestures to signify valor.

8. Adbhuta (Wonder & Amazement)

- Mudras:

- Tripataka — used with wide eyes to indicate surprise.

- Hamsasya — to show delicate, awe-inspired touches.

- Example: Portraying a child marveling at a magical event by expressive hand shapes and lifted fingers.

9. Śānta (Peace & Tranquility)

- Mudras:

- Anjali (hands folded together) — a gesture of prayer and calm.

- Shikhara (thumb raised, other fingers closed) — symbolizes stability and peace.

- Example: Representing meditation or divine blessing through calm, composed mudras and serene facial expressions.

Influence of Rasa Theory on Modern Indian Cinema and Theater

The Rasa theory has profoundly influenced the narrative style, acting methods, and emotional engagement strategies in Indian cinema and theater.

1. Acting and Expression

- Early Indian cinema actors often trained in classical dance or theater, using abhinaya techniques from Natya Shastra to convey emotions powerfully.

- Stars like Dilip Kumar (known as the “Tragedy King”) expertly portrayed Kāruṇya (compassion) and Raudra(anger) rasas, connecting deeply with audiences.

- The use of exaggerated expressions and clear emotional cues to evoke specific rasas remains common in Indian films, especially in melodramas.

2. Storytelling Structure

- Indian films frequently revolve around emotional arcs designed to evoke multiple rasas — from romance (Śṛṅgāra) to heroism (Vīra) to comic relief (Hāsya).

- Scenes are often choreographed to build rasa climaxes, where the audience is fully immersed in the emotional journey.

3. Music and Dance Sequences

- Dance numbers in Bollywood and regional films are often grounded in classical or folk dance traditions, consciously or unconsciously tapping into rasa to amplify mood.

- Songs embody the essence of a rasa — love songs for Śṛṅgāra, devotional songs for Śānta, or energetic beats for Vīra.

4. Theater Influence

- Indian theater, both traditional and contemporary, uses rasa as a foundation for direction and performance.

- Directors consciously craft plays to evoke specific rasas at different points, guiding the audience’s emotional journey and deepening their engagement with the narrative.

Acknowledgment:

I would like to acknowledge the works of Bharata Muni and scholars such as Manomohan Ghosh, Kapila Vatsyayan, G.K. Bhat, Leela Venkataraman and Ananda Lal whose translations and interpretations of the Natyasashtra have greatly contributed to the understanding of classical Indian theatre and dance. Their research provided the foundational knowledge for this article.

You might like to read >>>